In the dry heat of late African morning, a zebra raises its head from grazing. Its ears twitch nervously as its nostrils flare, catching the scent of a predator. Nearby, a lithe impala tosses its long, twisted horns in agitation. Others in the herd pick up on their unease, tensing and stamping their feet.

Thirty yards away, camouflaged in the dull yellow grass, a lioness rolls her powerful shoulders. She spent more than an hour stalking this close to the mixed herd. She can feel the tension in the herd ahead; if she doesn’t act soon, they’ll bolt.

Suddenly, a car horn blares. The sound sends the herd over the edge, and they scatter, leaving the huntress in a cloud of dust.

A quarter mile away, a giraffe watches the herd thunder south toward the ancient migration routes these creatures have travelled for generations. As the giraffe returns to feeding on an Acacia tree, it squints from the light reflecting off a nearby skyscraper.

Zebras in Nairobi National Park. Photo by Grace Nandy

A Land of Contrasts

In many ways, Nairobi National park is a microcosm of the rest of Kenya. The wild, ancient beauty of a park home to nearly every creature in The Lion King butts up against the most developed city in East Africa. From a geographical perspective, that balance extends to most of the country.

Famed for having some of the most beautiful beaches in Africa, Kenya’s coastal lowlands extend westward into one of the world’s more fascinating geological features: the Great Rift.

The Great Rift is a series of raised titanic splits in the landscape that transverses several countries. Tectonic separation beneath the Earth’s crust pushes enormous areas of the crust up relative to the surrounding land. In Kenya, that bulge creates resplendent highlands in the west. Home to many extinct and dormant volcanoes, the profound changes in elevation mean that despite lying directly on the equator, Kenya is home to several different climates. Mount Kenya, for which the nation was named, is often white with snow!

Tsavo East National Park. Photo by Damian Patkowski

The varied landscape and wide-ranging fauna have drawn people from all over the world to visit Kenya’s acclaimed wildlife preserves. In fact, Queen Elizabeth got the news that she had become Queen while visiting a preserve in Kenya!

The People

The allure of the land has been a defining feature of Kenya’s storied history. Even the famous tribe of lion hunters, the Maasai, didn’t migrate into their home in the highlands until the 18th century.

Long before colonisation, Kenya was a borderless land in greater East Africa, home to dozens of local tribes. All that began to change when the major port city of Mombasa was built around A.D. 900. An important trade stop in the Indian Ocean, Mombasa started to export things like ivory and sesame seeds, drawing foreign explorers deeper into the land.

Around 1500, the Portuguese built a fort in Mombasa that gave them dominion over the area for over a century until Arabs besieged it and took control. Arab control brought many changes to Kenya, including heavily influencing local languages (Swahili, and much of its vocabulary, is derived from Arabic). Unfortunately, Arab rule also brought a drastic increase in the slave trade that lasted well into the 19th century.

It was then that the British gained control. British leadership recognised Kenya’s potential as a colony and invested heavily in railroads and infrastructure, even building what would become Kenya’s capital city of Nairobi. They also brought in white settlers to operate vast tea plantations.

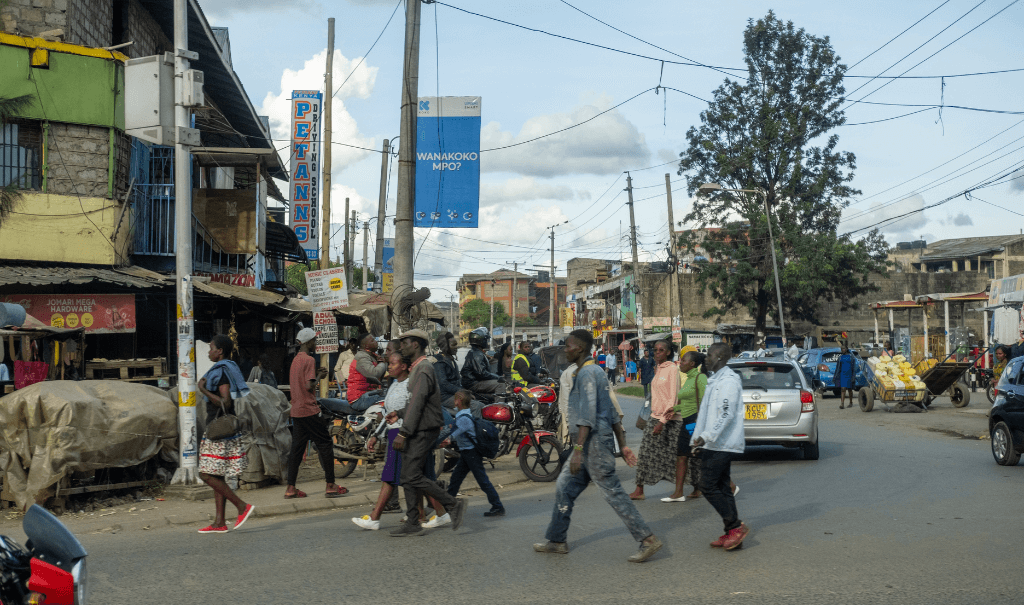

Nairobi, Kenya. Photo by Nicholas Gray.

These settlers displaced local peoples or hired them for exceedingly low wages. To make matters worse, after pushing native Kenyans out of prime farmland, the British government imposed heavy taxes that did not extend to the white settlers. That inequality, combined with the harsh treatment of native Kenyan workers, reached a breaking point in 1952.

The Mau Mau uprising was one of the darker moments in Kenya’s history. Militant groups of local tribes committed acts of unspeakable brutality against any they thought were British sympathisers, killing almost 20 times more local Kenyans than Europeans.

The disproportionate British response was equally barbaric: they threw over 10,000 Kenyans into forced labour camps and subjected them to starvation and torture. Though their response stopped the rebellion, it caused British leadership to rethink their strategy in East Africa.

Despite being an urban hub for the country, Nairobi is home to Nairobi National Park, a common jumping-off point for safari trips elsewhere in the country. Photo by Mustafa Omar.

Kenya gained independence in 1963. While the country had a few growing pains afterward, the democratic nation finally formed a coalition government in 2010 after drafting a new constitution. Kenya now boasts one of the fastest-growing economies in East Africa. Despite still being a lower-middle-income country, a recent Pew study indicates that Kenyans are hopeful about the future.

Challenges

Kibera, a division of Nairobi, is Africa’s largest slum and one of the largest in the world. “File:Nairobi Kibera 04.JPG” by Schreibkraft is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0?ref=openverse. No changes were made to this image.

Optimism notwithstanding, the CIA estimates that 36% of the population lives below the poverty line. That fact is evident in Kenya’s slum communities. Slums can be expansive, often containing separate villages within them. These close-knit communities have adapted to survive separately from the surrounding cities, often operating with their own unique economies and leadership structures.

The poverty prevailing in these slums is unimaginable to many Westerners. The people who live there face a day-to-day struggle for survival. Cut off from city-supplied services, water is often contaminated, and electricity is severely limited. Sickness and malnutrition abound; for many, just getting their next meal is an uncertainty.

Children are at particular risk in larger cities. Poverty, violence at home or the loss of parents (particularly due to AIDS) has led to a significant population of children on the streets. Public stigma against these children and a lack of social welfare programs means they are left uncared for and often abused. Trapped in desperation, many may become addicted to drugs at a startlingly early age or suffer sexual violence by community members. Others often eventually begin selling themselves to survive.

Another problem is how socially acceptable child prostitution has become, especially along the coast. According to the UN, one in three girls between the ages of 12 and 18 engage in casual sex work in Kenya’s coastal region. The practice has become so normalised that shopkeepers, neighbours and other local citizens turn a blind eye to it, especially if it appears to help the local economy. It’s not uncommon for a girl to sell herself for a single U.S. dollar.

We are already starting to help these children. During the pilot phase of our project in Kenya, we rescued 125 children from sexual exploitation, over half of whom were under 15 years old. Many were forced to sell themselves simply to get enough food to survive. Some of the other children we helped were rape victims, forced into child marriage or exposed to the sex industry through a parent.

Kids running at a Destiny Rescue home in Kenya

Changes

It’s exciting to witness the change in the children we’ve rescued. Many have joined foster homes and are experiencing parental love in a tangible way for the first time in their memory.

The abuse and neglect they’ve endured have left a terrible mark, but the healing is just as real. One foster father spoke of how two boys in his care, conditioned by fear of starvation on the street, ate every scrap of food in his home on their first day. As they grew accustomed to being loved and cared for, they began to understand that breakfast would be waiting when they woke, followed by lunch and supper.

Parents recount how closed-off and sceptical kids are right after rescue before they eventually open up, allowing their repressed but beautiful personalities to shine. Another child told her foster parent how thankful she was to be able to wake up, drink tea and go to school.

The children we’ve rescued are making progress, but thousands are still on the streets, suffering from damaging neglect and enduring unthinkable abuse just to get their next meal. Join us in giving these children what they never knew they were missing: childhood.

Survivors participate in an activity during Trauma Counseling

US & International

US & International New Zealand

New Zealand United Kingdom

United Kingdom